Ten years ago, the Wicked Witch of the West’s granddaughter flew out of Oz. She had Elphaba’s broom, and Gregory Maguire sent her off with a sentence that echoed the beginning of Elphie’s story, all those years ago.

A mile above anything known, the Girl balanced on the wind’s forward edge, as if she were a green fleck of the sea itself, flung up by the turbulent air and sent wheeling away.

Not a Witch, but a Girl; not a fleck of land but of sea; not a mile over Oz, but a mile over anything known. But Out of Oz ended not with Rain in flight, but with a brief coda that mused on “A welcome amnesia, our capacity to sleep, to be lost in the dark. Today will shine its spotlights to shame and to honor us soon enough. But all in good time, my pretty. We can wait.”

The coda was about a world waking up, about impressions and hypotheses. It didn’t entirely make sense when Out of Oz was published, but now it serves as a wisp of connective tissue to The Brides of Maracoor, which brings back Rain, Maguire’s other green girl, and drops her into an entirely new world—one that is on the edge of being rudely awakened.

On the island of Maracoor Spot there are seven brides. Every morning, they cut their feet and let the salt water sting; every morning, they twist kelp into the nets that shape time. When one dies, the Minor Adjutant—the only other person they ever see—brings another baby from the mainland to be raised as a bride. Their job is all-important, and not quite what it seems.

If you are the kind of reader who likes to know how things work, you may have questions: Who were the first brides? Who built the temple? Who taught them to make cheese, to take care of themselves, to twist the kelp, to cut their feet? Why do they know the concept of hospitality when they are never visited, never even seen except by Lucikles, the aforementioned Minor Adjutant, who checks in annually?

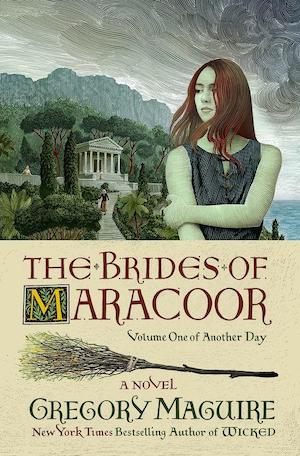

Buy the Book

The Brides of Maracoor

Gradually, Maguire begins to drop hints. But this is the first book in a new series, and he leans into that newness, calling a world into being piece by piece: the sea, the forests, the birds that swarm a ship. From the lives of an amnesiac young woman, a curious and ignorant child, and one selfish Minor Adjutant, he weaves a story full of change, though we can’t yet see what form that change will take.

Rain, who doesn’t remember much about where she came from, is us, the readers, the newcomers to this place. As Mari Ness wrote, reviewing Out of Oz, Rain has been shaped by abandonment. But now she has been abandoned by her memory, too, though that hardly makes her a blank slate. When she washes up on Maracoor Spot, she finds seven women who have been told a story about how they need to injure themselves and wrangle time. Even Rain knows something is awry here. With her, we peel back layers, watch the young bride Cossy try to wrap her mind around new things, watch her hunger for new experiences. Rain is just a lost girl; Rain is an education. It’s possible to want more than the life given to you.

The brides refer to their unexpected visitor as the Rain Creature and are skeptical of her and her Goose companion, Iskinaary. She’s not a bride, but only brides live on Maracoor Spot, so does that make her a bride by default? If so, they are the wrong number. There is no protocol for this.

And so Lucikles finds them, though they try to hide Rain from him. Maguire takes us through the days of these characters with grace and specificity, vividly shaping the finite world of this tiny island, which gives the brides everything they require and takes everything from them in turn. Rain is the thing that rarely comes to Maracoor Spot: change. Her arrival is a minor spot of chaos that echoes across Maracoor, a nation run by petty bureaucrats who are perfectly happy to blame the stranger for everything that happens in her wake.

And much happens. An unknown army invades the capital, behaves strangely, and vanishes. There are rumors of flying monkeys. It’s all simply too much for a Minor Adjutant who just wants to do his job, be on schedule, and make life good for his son, though he professes to have no favorites among his children.

Lucikles would be a bore in person, but as a character, as a pivot point, he is a horribly, quietly ordinary cautionary tale. He is the kind of man who thinks himself good but may just ruin everything through his sheer unwillingness to involve himself, to think of something bigger than his family, to demonstrate an iota of imagination. His resistance—to making a choice, having an opinion, challenging any of his world’s norms—wreaks havoc on the brides’ lives. (Though, to be fair, they do some of that themselves.)

The Brides of Maracoor feels eerily familiar, a story steeped in classics, full of names that echo or borrow from Greek mythology, and with a mythology of its own that’s just sideways from what we know. It sometimes calls to mind Circe, exiled on her island, but at least she knew why she was there. Maracoor Abiding is somewhere between our world and Oz, a little bit of both, where birds might look like tiny witches and mysterious roars echo across an island—but men handily ruin women’s lives without hardly thinking about it, creating structures and myths that maintain their own power.

Maguire, after all these years, is still thinking about evil, though of a very different stripe. Sharp and wry, funny and pointed, he writes in Brides with a certainty and a sort of world-sized elegance, creating something new from scraps of the cloth he worked for years. He remains a master of a specific sense of intimacy amid scale, able to craft precise moments of fallibility, of humans picking our way through our lives, against the fate of nations and the endless sea. What lingers most vividly are moments of character—Cossy’s indignation, Rain remembering a name, Lucikles failing his son—and the moments when nature does what it will, regardless of the whims of men. Storms come through. A Goose shits on the floor. Something roars in the night. You can know so much, and yet almost nothing at all.

Early in the book, Maguire introduces a word: ephrarxis. “Nostalgia for something that had never been,” he defines it. Maracoor Abiding is steeped in this feeling, and The Brides of Maracoor is, too. I feel like I went somewhere I can never go back to, or heard a story that can’t be retold. What that means for the next two books I can only begin to imagine.

The Brides of Maracoor is published by William Morrow.

Read an excerpt here.

Molly Templeton lives and writes in Oregon, and spends as much time as possible in the woods. Sometimes she talks about books on Twitter.